DENVER — New research out of the University of Colorado Boulder shows that breathing in Colorado’s crisp mountain air is more a luxury than a guarantee.

In fact, researchers found minority communities and those with lower household incomes are more likely to live in neighborhoods near facilities that emit bad smells.

"There are significant health impacts from experiencing bad odors," University of Colorado Denver Assistant Professor Priyanka DeSouza said. "Be it stress, be it mental health issues, sometimes physical health symptoms as well."

Assistant Professor DeSouza was also a critical part of the CU Boulder research. She is particularly concerned about people under-reporting the issue and communities that are disproportionately impacted by this problem do not always feel like their voices are being heard.

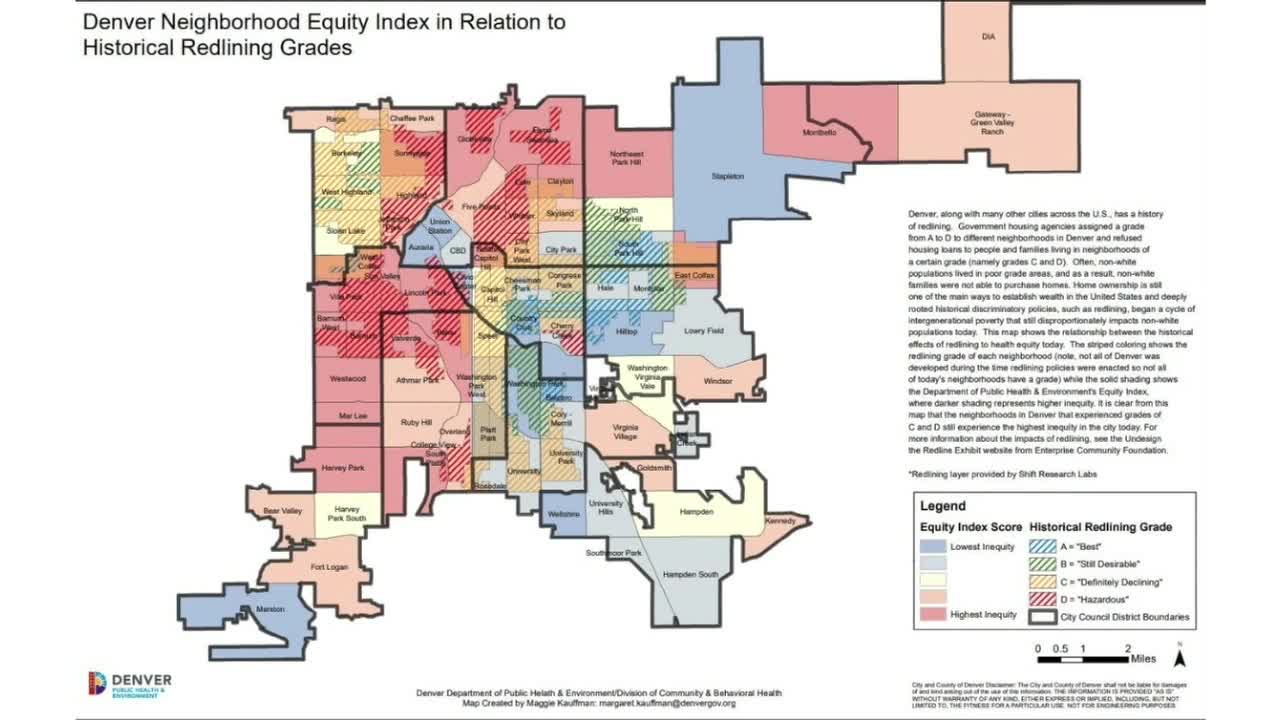

"Although the majority of those facilities are located in Denver's"inverted L" neighborhoods that have experienced redlining and comprised of majority minority populations and low income populations," DeSouza said. "We found that odor complaints were distributed widely across Denver County, and in fact, we saw a significantly higher number of complaints in gentrifying areas."

The research explained the impacts of redlining and gave some historically perspective.

“After the Great Depression, the U.S. government implemented a racist and discriminatory policy that designated neighborhoods with racial and ethnic minority residents as high-risk, or 'red' for mortgage lenders," the research reads.

In Denver, these neighborhoods are along Interstate 70 and Interstate 25, and home to more minority communities. There are previous studies that show people in these areas are exposed to more air pollution.

Because of research like this, the City of Denver changed its air pollution control ordinance in 2016. It now requires facilities, including pet food and marijuana growers, to submit an odor control plan if they get five or more complaints within a month.

Researchers found 265 facilities in Denver had to submit one of these plans, as of 2023. More than 96% were marijuana growers, processors and manufacturers. The rest were pet food manufacturing, oil refining and construction.

"Odors are tricky because they are not federally regulated," Gregg Thomas, with the Denver Department of Public Health and Environment (DDPHE), said. "The state does have regulations for odor. It's really designed around big industrial and agricultural. So it's not really geared to address odors at the urban level. That's why we have, over the years, worked on creating nuisance provisions. We investigate, and we validate those, and oftentimes that includes field measurements. The challenges is field measurements can come after the complaint is received, and by the time you get out there, things are things have changed."

Thomas said one of the large facilities they worked with spent nearly $10 million on odor control over the last decade. He did also say it's tricky, but it requires working with complicated manufacturing. Sometimes equipment breaks down or weather conditions are conducive to poor air quality, including odors.

Now that this new data is out, DDPHE said it will be taken into account over the next year and a half.

"We plan to use that to guide our next ordinance revisions," Thomas said. Which we're hoping for in late 2026 so there's a lot of stakeholder engagement that will need to be done over the next 18 months to move that forward."

Denver7 is committed to making a difference in our community by standing up for what's right, listening, lending a helping hand and following through on promises. See that work in action, in the videos above.