DENVER – Colorado’s middle class has shrunk since 2000 as its lower- and upper classes grew—due in part to wages that haven’t kept pace and rising costs of living and education in the state, according to a new study released last week from the Bell Policy Center, the Colorado Trust and the University of Colorado Denver’s School of Public Affairs.

The study, “Colorado’s Middle Class Families: Characteristics and Cost Pressures,” was commissioned by the Bell Policy Center and authored by CU Denver’s Todd Ely, PhD and Geoffrey Propheter, PhD.

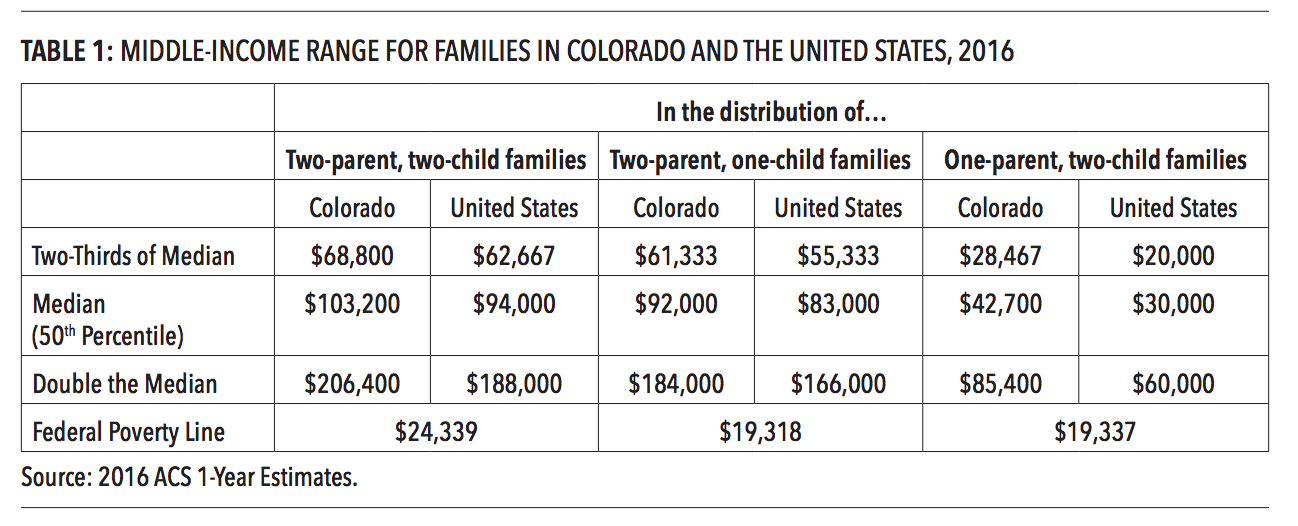

It uses the Pew Research Center’s income-based definition of the middle class of a family that makes between two-thirds and double the median family income to define Colorado’s “middle income.” The researchers, for the study, used the 2016 statewide median income of $59,000 to make the baseline “middle income” class families that earn between $38,900 and $118,000 a year.

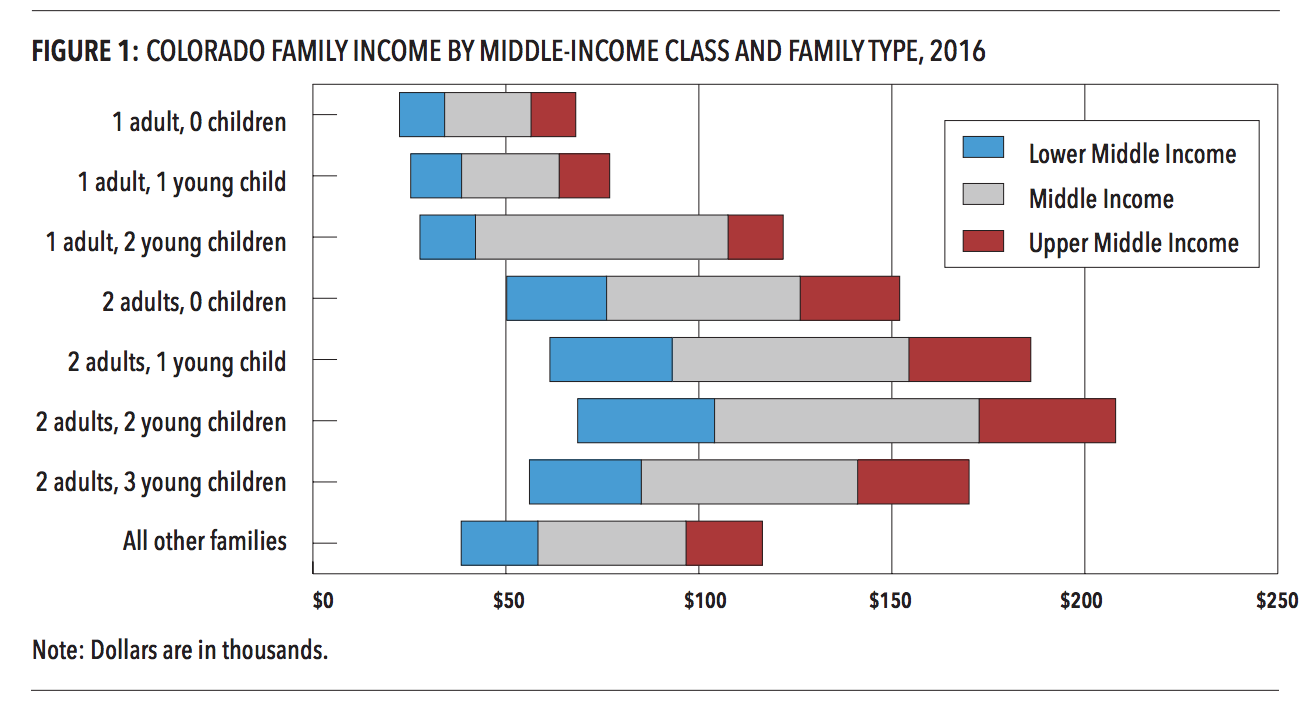

But they also established levels for “middle income” for various types of families—from single adults without children to two-adult, three-child families.

The research shows that at all levels of the “middle income” level, Coloradans have to earn more to be part of that income class than they do, on average, in the rest of the United States.

As of 2016, just fewer than half (49.6 percent) of Coloradans were considered middle income families—down from 53 percent in 2000. The lower-income class grew over that time period, from 30.5 percent in 2000 to 32.1 percent in 2016. And the upper-income class grew from 16.5 percent of the population in 2000 to 18.3 percent of it in 2016, according to the study.

“It is noteworthy that while the decline in the percentage of families falling in the middle-income class was exacerbated by the Great Recession, the trend existed before the economic downturn,” the study says. “The middle class decline is offset by gains in the share of Colorado families identified as lower and upper income in 2016.”

The study shows that Colorado’s 6.4 percent decline in the middle class ranked 11th in the nation in terms of negative growth. Alaska saw the highest negative growth over that period, at -9.3 percent. But Washington, D.C. was the only “state” that saw positive middle income growth from 2000 to 2016; it saw growth of 4.9 percent. Wyoming was second in middle income growth, though its share was -0.7 percent.

That middle-income class is dominated by single adults and two-adult families without kids, which make up 58.5 percent of that population. They are also generally older, with 54 percent being at least 51 years old.

The study also shows that Colorado’s middle and upper income classes are predominantly white and that minorities are underwhelmingly represented in both of those classes. The study found that family representation for Hispanic and black families falls as the income class increases in Colorado.

“Differences in racial representation across income classes point to a middle-income attainment gap, and, further, the persistence of the gap over time reflects an increasing difficulty for minority families to enjoy the same middle class lifestyle as white families,” the authors wrote.

The researchers say they expect that trend to continue and say that the gaps extend to other facets of living aside from income.

“The persistence of a middle class attainment gap signals other social outcomes that vary systematically by race, such as education, have far-reaching implications for the economic trajectories of Colorado’s minority families.”

And the researchers say that education is one of the most important factors for Colorado’s trying to make middle income. Fifty-seven percent of the state’s middle-income families had at least one adult with a bachelor’s degree or higher—an increase from 2000, when that rate sat at just 41 percent. But they said that those increases in people with four-year degrees has risen comparatively in the lower- and upper-income classes as well.

But the researchers warned that getting a bachelor’s degree might not be good enough for people hoping to reach the middle-income class either.

“Examining graduate degree attainment makes a stronger case that not only is education important for being a middle-income family or higher, but having a bachelor’s degree alone may not be enough to reach or sustain being middle income,” the report says. “A quarter of middle-income families and nearly half of upper-income families now have at least one graduate degree.”

People working in the health care and education industries were most likely to be in the middle-income class. Between 2000 and 2016, health care and professional, scientific and technical industry workers saw the greatest percentage increase in terms of the number who were in the middle-income class.

And the urban-rural divide is also shown in the middle-income rates. Urban Coloradans needed to make between $36,800 and $111,500 to be considered middle income in 2016, while rural Coloradans needed to make between $30,900 and $93,6000, according to the report.

The median rural family income was 19 percent lower than those of urban families.

Part of the growth of the lower-income class comes from people moving to Colorado, the study says.

“[I]n 2016, for each lower-income family who left the state, 1.6 lower-income families entered. For middle- and upper-income families, the enter-to-exit ratio is 1.3 and 1.2 respectively. The state’s population growth has been, on average, 1.6 percent a year since 2000, according to the study.

But still, the study makes quite clear its findings: “Fully achieving the middle class lifestyle detailed here is impossible for most family types with actual middle-income levels in Colorado,” it says.

It suggests some options for people: spend less, work and earn more, borrow, get help from family and friends and tap into existing savings. But it also acknowledges that “there are a limited number of strategies with which to reconcile these family budget deficits.”

Further, the report says that “the hypothetical budgets for middle class families in Colorado demonstrate incomes generally fall below the amount needed to fulfill all of the expected aspirational and non-aspirational items.”

The report shows that Colorado has more debt per capita compared to the rest of the U.S., on average, and more student loan debt as well. It also shows that the states consumer debt per capita to median household income ratio for 2016 was third-highest in the country—just behind California and Washington, D.C.

“At a high level, it is clear the real growth in family income has failed to keep pace with a number of the key costs of a traditional middle class lifestyle,” the report says. “Most prominently the price of public higher education, health care costs, and housing values have increased at a much higher rate than income for our three selected family compositions.”

In its conclusions, the researchers suggest a handful of policy changes lawmakers should work toward in order to support the middle income class.

“Based on our findings, targeted policies can be developed along the dimensions of 1) identifying and supporting jobs that sustain middle class lifestyles; 2) educational strategies to create pathways to the right occupations or, in the case of multi-head families, combinations of occupations; 3) addressing racial inequity; and 4) determining where the public sector can provide high return investments to ease entry into and maintain a lasting presence among the middle class.”

And despite those suggestions, the researchers wrote that there was one facet they couldn’t address: what exact tradeoffs can be made by people to get into the middle class.

“This study could not shine a light on the sorts of tradeoffs Colorado’s families make in order to attain and retain a middle class lifestyle, because such information requires a qualitative perspective lacking in federal survey data,” the report concludes.

“If we know the tradeoffs families are making to access and maintain a middle class lifestyle, then lawmakers have a better sense of which public policies can help families,” Propheter said in a news release. “For instance, we know child care is expensive, and programs partially subsidizing daycare provide financial relief for families who might otherwise forego children or make other sacrifices that keep them out of the middle class indefinitely.”